🎤 Interview by “D-Man,” CTF Inmate Correspondent

I never know how many more Sundays we have left on this journey—this journey into the life of Cain. Each moment feels fleeting, so I ask him everything I can, writing it down as faithfully as possible. It always feels like too much, and yet somehow never enough. For you, the reader, I wonder: have you been here since the first episode of Sundays With Cain? Or did you join us somewhere along the way and still need to catch up? Have you reread certain passages, trying to soak in the meaning? Have you shared your favorite story with someone else? Did a part of Cain’s journey resonate with you on a deeper level? Maybe you came for the fight stories. Maybe it’s his family struggles and bonds that draw you in. Maybe you’re fascinated by how trauma fueled his hunger for violence, or how he now works through healing, learning, and teaching techniques for peace. Maybe you’re just waiting to hear another Bob Cook mishap. Whatever your reason for being here, thank you. Each episode brings us closer to Cain. Closer to understanding the meaning behind his war. Closer to seeing what lessons a fighter, a father, a son, a brother, a friend, a hero, and a prisoner can pass down in times of peace.

This Sunday begins, as always, with me joining Cain “The Healer” at the Ascension Breath Work class. Every time I take part in holotropic breathing, something inside me changes. Layers peel away, and I no longer see myself as the abandoned child, the delinquent, the addict, the prisoner, the absent father, or the failure I once thought I was. In those moments, I see the truest version of myself—calm, strong, patient, at peace, and deeply connected to something all of us carry within. The changes feel real in my body: less pain in my sciatic nerve, deeper breathing, more restful sleep, even a strange metallic taste in my mouth that tells me something is shifting. And yet, no matter how I try to explain holotropic breathing—even if I spoke until I was blue in the face for a thousand days straight—I could never capture the experience in words. You have to try it yourself. A friend of mine recently came to his first class. He lay there crying, unable to speak for a long while afterward. Finally, he told me, “It felt like all the suppressed emotions of my life came out at once. I was peeling them back like an onion.”

With that in mind, I asked Cain if people should try holotropic breathing on their own. He said, “Yes, they can start with something simple—maybe three minutes. Put on one song, lie down, and just go at your own pace. Gauge how your body reacts.” When I asked him how he would guide someone through their first time, he answered, “I’d tell them to go for it. Know that all the strange sensations—your muscles locking up, your hands or feet tightening—are normal. The work is the work. Keep pushing your breath in deep, out deep, steady with the rhythm of the music. ‘One,’ push it all out. ‘Two,’ draw it all back in. No pauses. One, two, one, two—just keep going until the song ends. Longer is better, but it’s always about your comfort level. If you can push, then push. Everyone’s pace is different, whether in class or at home.”

When I asked Cain if there were any updates on other prison activities—his plumbing class, choir, football team, or plans to bring Breath Work to the prison next door—he shook his head. “No, but I did meet with a lawyer. We talked about wrongfully accused inmates. Some men here just want their cases heard.” He paused, then added, “It’s kind of what we’re doing now—sharing stories, shining a light, showing that the system needs reform.”

That led me to ask about conversations with his fellow inmates after their interviews—Junior, Elio, and Kirk. Cain smiled. “Kirk is quiet. He just smiles. Elio jokes about being famous now. Junior grins every time we bring up his interview.” I asked why he chose Junior to lead class in his absence. Cain replied, “I let it happen naturally. He showed interest and asked to help. He’s got a calling as a healer.”

I shifted gears and asked about prison food. Cain laughed. “When I first got here, I thought the food wasn’t even real. It looked engineered—bright colors, bland taste. It was 80% right and 20% off. I kept thinking, ‘What am I eating?’ But now I’ve gotten used to it. Spaghetti tastes like spaghetti.” I asked if he ever cooks. “Oatmeal,” he said, then smirked. “But people give me food all the time. On my birthday, I ate burritos for breakfast, tostadas and ice cream for lunch, and someone even made me apple-chocolate doughnuts.” So if any of our readers are concerned about Cain withering away in lockdown, I think it's safe to say that you can put your mind to rest.

We drifted into his childhood memories. Cain is the youngest of three. His sister is four years older, his brother two. His first memory of his sister is her walking him to school. “I remember asking her to stay and play with me,” he said. His first memory of his brother was more painful. “I got a skateboard, even though my mom said no. It had a big eye in the middle, with designs around it. We were outside our apartment in Yuma. I was on one knee, and my brother pushed me. I flew forward, smashed my chin into the concrete, and needed stitches.” Cain tilted his chin to show me the scars—two of them, though one carried more meaning than the other.

We touched on his first family pet—a German Shepherd named Charlie who lived to old age—and his first memory of school. “Kindergarten. My mom walked me in. Lots of kids were crying. She brought me to a boy who was crying too, and I played with him. He was my friend for a couple of years, but we moved a lot. I don’t remember his name. I went to five different elementary schools, one in Eloy. Moving made it hard—always making new friends, always leaving old ones behind.”

Then we returned to his fighting career. After the Kongo fight, Cain faced Ben Rothwell. He was undefeated, a new dad, but unhappy with his performance. Back in the gym, he focused on defense and head movement. That’s when Daniel Cormier showed up. Cain grinned, telling the story. “DC had just finished his Olympic career. Javier told me in Spanish, ‘Take it easy on this guy.’ Daniel heard him and shouted, ‘No! Tell him, let’s go!’ "So we sparred, and right away I kicked him in the nose. Blood everywhere. That was the end of our first session.” Cain chuckled. “Javier used to tell me, ‘If you break your toys, you won’t have anything to play with.’”

After Rothwell, Cain began traveling to Mexico before and after every fight. Dana White had pitched him the idea of building his brand there. “But it wasn’t well received,” Cain admitted. “Boxing ruled Mexico. People said, ‘You’re born in America, your Spanish isn’t great—what are you trying to sell us?’ They called us human cockfighters.” Still, he persisted, running a grueling schedule of interviews from dawn until night every time he landed in Mexico City.

Against Rothwell, Cain won by TKO in the second round. He only ever heard Bob Cook’s voice in his corner—loud enough for the whole arena. Still, he wasn’t satisfied. “The media called me ‘Pillow Hands,’” Cain said with a shrug. There was even a meme of him with pillows for fists.

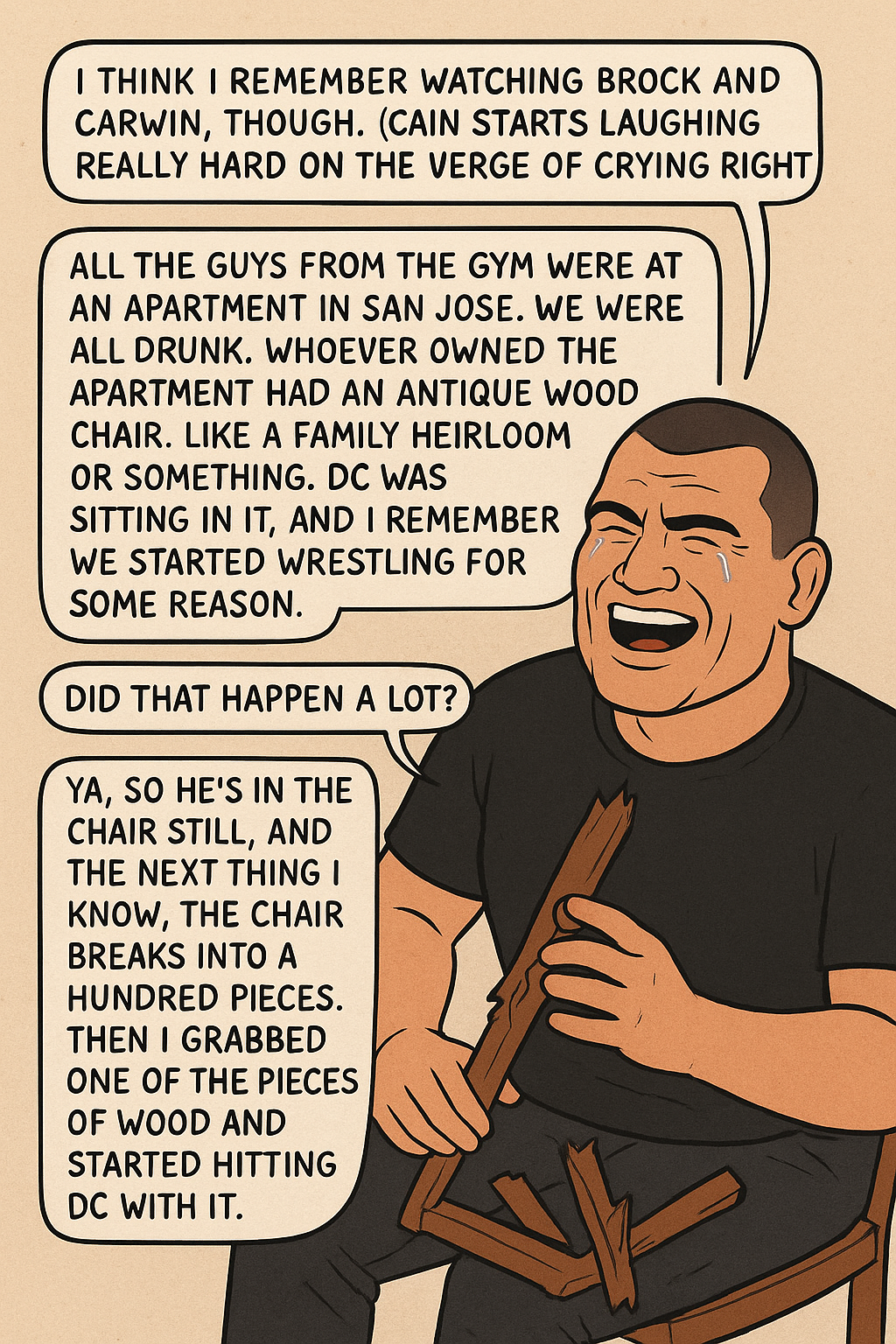

I asked if he remembered watching Brock Lesnar beat Randy Couture. He couldn’t, but he remembered watching Brock fight Shane Carwin. Cain laughed so hard he nearly cried. “We were all drunk at an apartment in San Jose. DC sat in an antique wooden chair. We started wrestling. Next thing I know, the chair shattered into a hundred pieces. I grabbed a chunk of wood and started hitting DC with it.” He laughed again, shaking his head.

Later that night, during yard time, we walked the track together. Cain suddenly blurted out, “Quick Mix.” I asked what he meant. He smiled. “Strawberry Quik. I loved it as a kid. Always had to have it for breakfast.”

Before I left, I asked him our weekly fan question, this one from Lisa Marie. Her son had once attended a wrestling camp with Cain, and she wanted to know: What advice do you have for young men growing up in troubled times, feeling lost? Cain answered, “Even when they feel lost, they’re not lost. It’s their path, their journey. They just need to find something that speaks to their heart. Something they’re truly passionate about.”

Lisa Marie also asked if Cain had any Bible verses he lived by. He gave two. First, Luke 23:46: “Father, into your hands I commit my spirit.” Cain said, “The last words Jesus said on the cross before he took his final breath. For me, it’s about the divine Father guiding me. There are no accidents. Everything is in order.” Second, Mark 12:28–30: “The Lord is one. And you shall love the Lord your God with all your heart.” Cain explained, “God is omnipresent. He is everything. The only time I ever felt lost was when I didn’t know myself. Once I learned who I was, I saw God in everything.”

And with that, another Sunday came to a close. Thank you for reading and sharing this journey. See you next week for more Sundays With Cain.